Ahmet Dogan1, Hasan Tahsin Gozdas1, Sıddıka Halıcıoglu2

1 Department of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology, Abant Izzet Baysal University Faculty of Medicine, Bolu,Turkey

2 Department of Radiology, Abant Izzet Baysal University Faculty of Medicine, Bolu,Turkey

doi: 10.5281/zenodo.11517566

Corresponding author:

Ahmet Dogan

Department of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology, Abant Izzet Baysal University Faculty of Medicine, Bolu, Turkey uzdrahmetdogan@gmail.com

Received: 4 June 2024

Revised: 7 June 2024

Accepted: 7 June 2024

Published: 7 June 2024

Cite as:

Dogan A, Gozdas HT, Halıcıoglu S. Varicella Zoster Virus Encephalitis in an Elderly Immunocompromised Patient. Med J Eur. 2024;2(3):22-24. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.11517566

ABSTRACT

| Varicella zoster virus (VZV) is the causative agent of chickenpox in childhood. Thereafter, it remains latent in the neural ganglia and may cause complications such as herpes zoster and, more rarely, meningitis and encephalitis in elderly or immunosuppressed patients. Cerebrospinal fluid examination, cell culture, molecular and serological methods and radiological findings are helpful in the diagnosis. Here, we present a VZV encephalitis case in an elderly corneal transplant patient. |

Keywords:

Corneal transplantation, varicella zoster virus, herpes zoster, encephalitis.

INTRODUCTION

After primary infection of chickenpox, which usually occurs in childhood, varicella zoster virus (VZV) remains latent in the dorsal root ganglia. Its reactivation in adulthood usually results in herpes zoster (shingles), but different clinical pictures such as encephalitis, meningitis, cerebellitis, myelitis and cerebrovascular events may also be encountered [1-3]. Immunosuppression, history of previous hospitalization and comorbid diseases are risk factors that increase the likelihood of VZV infection in central nervous system (CNS) (4). However, rare cases of VZV encephalitis in immunocompromized young patients have been reported. There are also studies in solid organ transplant recipients (5-7). However, to our knowledge, this is the first case of VZV encephalitis developing after herpes zoster in a corneal transplant patient.

CASE

A 74-year-old man was admitted to the emergency department with fever, chills, impaired consciousness and slurred speech for 2 days and painful vesicular skin lesions on the scalp and left leg (Figure 1A, 1B) for the last 7 days.

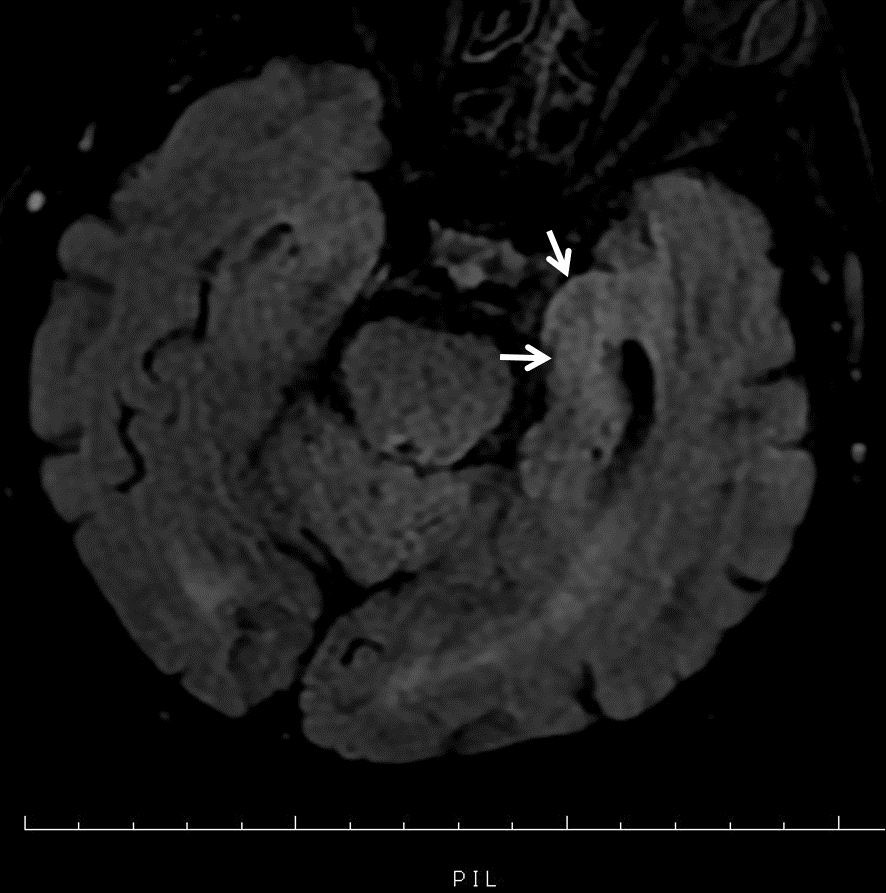

On physical examination; There is no time-place orientation, consciousness is confused, there is neck rigidity, fever is 36.1 C, blood pressure arterial: 130/80 mmHg, pulse: 102/min, saturation: 96. Other system examinations were normal. He had a history of diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and previous corneal transplantations. It was learned that he underwent corneal transplantation 4 times before and the last transplantation was performed 1 month ago. He had been using mycophenylate mofetil 500 mg twice a day and prednisolone 16 mg once a day as immunosuppressive treatment after transplantation. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging showed T2 hyperintensity in the left medial temporal lobe (Figure 2) consistent with encephalitis.

Figure 1A and 1B. Painful vesicular skin lesions on the scalp and left leg.

In cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, white blood cell count was 30 cells per mm3 and gram staining showed 3-4 leukocytes in each area. CSF biochemistry revealed glucose: 96 mg/dl (concurrent blood glucose: 176 mg/dl) and protein: 4475.20 mg/l (n: 150-400 mg/l). Varisella Zoster Virus IgM: 0.3 (n:0-1.1) was negative, and VZV IgG: 3.03 (n:0-1.1) was positive in serum, however VZV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was detected positive in CSF. Then, the patient was diagnosed with VZV encephalitis and acyclovir 3*750 mg intravenous was started. During follow-up, he was transferred to the intensive care unit due to exacerbation of impaired consciousness. Acyclovir was stopped on day 29. During intensive care unit hospitalization, he received various antibiotic treatments due to growth pathogens in various cultures. Consciousness cleared. The rash regressed. Approximately at the end of the second month of intensive care hospitalization, the patient was externed to the palliative service.

Figure 2. Hyperintense signal in the left medial temporal lobe in magnetic resonance imaging.

DISCUSSION

Viral encephalitis is still an important cause of serious morbidity and mortality. However, the etiologic diagnosis remains unclear in most of these cases making rapid diagnosis and treatment important. Duration of complaints, exposure status, cerebrospinal fluid findings and radiological imaging are guiding in the diagnosis (8). In a study in which 117 cases of CNS infection caused by VZV were examined, it was found that the most helpful diagnostic tests were CSF findings and VZV PCR in peripheral blood (9). Serology was not helpful in the diagnosis of our case, but radiological imaging and CSF findings were helpful. Long-term use of immunosuppressive agents due to corneal transplantation might have affected the serological results. Radiologic imaging is not as helpful in cases of viral meningitis as encephalitis. In this situation, the difficulty in rapid diagnosis and initiation of treatment increases (10). Radiological imagings may give false results at a high rate in individuals in whom intracranial pressure does not increase significantly (11). Another important factor preventing the direct use of radiological imagings in the initial diagnosis is that it may lead to unwanted delay in treatment (12). As in our case, such disadvantages increase the importance of PCR in the diagnosis. Studies have shown that PCR has >90% sensitivity in detecting the presence of many viral agents including VZV (13). In cases receiving antibiotic and antiviral treatment in the early period or in immunosuppressed cases as in our case, PCR may be more helpful in the diagnosis compared to other methods. In addition, new diagnostic methods are also being developed (14). Among these methods, Metagenomic Next Generation Sequencing method is a new and promising method that has the ability to recognize all pathogens in human samples simultaneously (15, 16). However, we do not yet have the opportunity to use such expensive new diagnostic methods in our country. While vesicular rash was generally reported in a single dermatome area in cases developing VZV encephalitis especially after renal transplantation, vesicular rashes were observed in two dermatomes in our case (17). However, it has been reported that VZV dissemination may sometimes occur without any cutaneous lesion. This may be because the virus may not reach the dermatome from the ganglia since T cells are especially affected in transplant patients (18). The elapsed time between the onset of symptoms and treatment start is important. The longer the time, the higher the risk of dissemination. Another important point is that VZV IG G positivity before transplantation in transplant patients may become negative after transplantation. Therefore, these seropositive patients should also be followed carefully in terms of VZV infection after transplantation. It should also be kept in mind that VZV encephalitis may develop in these immunosuppressed patients receiving low-dose antiriviral prophylaxis/therapy after this prophylaxis/therapy is discontinued. In immunosuppressed cases, intravenous acyclovir treatment for an average of 14 days (7-42 days) was sufficient. In cases who were using valacyclovir, a good response was obtained with 14 days of treatment (17, 19).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of Herpes zoster infection affecting two dermatomes after four corneal transplants followed by VZV encephalitis, a rare complication. In cases with immunosuppression, if herpes zoster is also present, it is necessary to be careful in terms of CNS involvement. Despite pre-transplant IG G positivity and low dose antiviral prophylaxis VZV encephalitis may sometimes develop. Also, the absence of vesicular rash should not mislead us. The time between symptoms and treatment is the most important risk for dissemination. Although serology was negative, PCR and subsequent radiological imaging were helpful in the diagnosis. Serology may not be useful immunosuppressed cases. New and promising diagnostic methods have being developed.

CC BY Licence

This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

REFERENCES

- Nagel MA, Niemeyer CS, Bubak AN. Central nervous system infections produced by varicella zoster virus. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2020;33(3):273-278. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000647.

- Erdem O, Ülkü A, Yanık A, et al. An Unusual Cause of Splinter Hemorrhages: Herpes Zoster Infection. Balkan Med J. 2023;40(5):378-379. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37519021/.

- Chirumamilla Y, Ajmal S, Subedi B, et al. Varicella Zoster Meningitis in a Young, Immunocompetent Patient Despite Initiation of Antiviral Therapy. Cureus. 2023;15(6):e39980. doi: 10.7759/cureus.39980.

- Omland LH, Vestergaard HT, Dessau RB, et al. Characteristics and Long-term Prognosis of Danish Patients With Varicella Zoster Virus Detected in Cerebrospinal Fluid Compared With the Background Population. J Infect Dis. 2021;224(5):850-859. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab013.

- Petrun B, Williams V, Brice S. Disseminated varicella-zoster virus in an immunocompetent adult. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21(3):13030/qt3cz2x99b.

- Kronenberg A, Bossart W, Wuthrich RP, et al. Retrospective analysis of varicella zoster virus (VZV) copy DNA numbers in plasma of immunocompetent patients with herpes zoster, of immunocompromised patients with disseminated VZV disease, and of asymptomatic solid organ transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2005;7(3-4):116-121. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2005.00106.

- Kang M, Aslam S. Varicella zoster virus encephalitis in solid organ transplant recipients: Case series and review of literature. Transpl Infect Dis. 2019;21(2):e13038. doi: 10.1111/tid.13038.

- Adarsha B, Rodrigob H. Diagnostic approach and update on encephalitis. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2022;35(3):231-237. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000832.

- Dyachenko PA. Varicella-zoster virus cns disease clinical features in ukrainian patients. prospective study. Wiad Lek. 2019;72(9 cz 2):1765-1768.

- Glimåker M, Johansson B, Grindborg Ö, et al. Adult bacterial meningitis: earlier treatment and improved outcome following guideline revision promoting prompt lumbar puncture. Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Apr 15;60(8):1162-9. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ011.

- Michael B, Menezes BF, Cunniffe J, et al. Effect of delayed lumbar punctures on the diagnosis of acute bacterial meningitis in adults. Emerg Med J. 2010;27(6):433-438. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.075598.

- Proulx N, Fréchette D, Toye B, et al. Delays in the administration of antibiotics are associated with mortality from adult acute bacterial meningitis. QJM. 2005;98(4):291-298. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hci047.

- Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(9):1267-1284. doi: 10.1086/425368.

- Piantadosi A, Mukerji SS, Ye S, et al. Enhanced Virus Detection and Metagenomic Sequencing in Patients with Meningitis and Encephalitis. mBio. 2021;12(4):e0114321. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01143-21.

- Leon KE, Schubert RD, Casas-Alba D, et al. Genomic and serologic characterization of enterovirus A71 brainstem encephalitis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7(3):e703. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000703.

- Graff K, Dominguez SR, Messacar K. Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing for Diagnosis of Pediatric Meningitis and Encephalitis: A Review. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021;10(Supplement_4):S78-S87. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piab067.

- Nabi S, Kahlon P, Goggins M, et al. VZV encephalitis following successful treatment of CMV infection in a patient with kidney transplant. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014206655. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-206655.

- Arvin AM. Varicella-Zoster virus: pathogenesis, immunity, and clinical management in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2000;6(3):219-230. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(00)70004-8.

- Umezawa Y, Kakihana K, Oshikawa G, et al. Clinical features and risk factors for developing varicella zoster virus dissemination following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2014;16(2):195-202. doi: 10.1111/tid.12181.