Sıtkı Selçuk Gökyay1, Hüseyin Gürkan Güneç2, Hasan Fehmi Ates3

1 Department of Endodontics, Istanbul University Faculty of Dentistry, Istanbul, Turkey. ORCID: 0000-0003-2660-6329

2 Department of Endodontics, University of Health Sciences Hamidiye Dental Faculty, Istanbul, Turkey. ORCID: 0000-0002-7056-7876

3 Computer Engineering, Özyeğin University School of Engineering, Istanbul, Turkey. ORCID: 0000-0002-6842-1528

Received: 11 June 2024

Revised: 14 June 2024

Accepted: 14 June 2024

Published: 14 June 2024

Keywords:

Deep learning, YOLOv4 program, dental diseases, tooth enumerations, panoramic radiographs.

Corresponding author:

Hüseyin Gürkan Güneç.

Department of Endodontics, University of Health Sciences Hamidiye Dental Faculty, Istanbul, Turkey.

gunecgurkan@gmail.com ORCID: 0000-0002-7056-7876

doi: 10.5281/zenodo.11582062

Cite as:

Gökyay S, Güneç HG, Ates HF. Application of an Artificial-Intelligence Algorithm for the Enumeration of Teeth and the Detection of Multiple Dental Diseases. Med J Eur. 2024;2(3):58-65. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.11655240

ABSTRACT

| This study aimed to evaluate the automatic detection of dental diseases as well as tooth enumeration in panoramic radiographs by artificial intelligence (AI). A total of 5,126 adult patients’ panoramic radiographs were labeled separately with tooth numbers and dental diseases and prepared for AI training. The “you only look once version four” program was used to test and train the deep learning model developed for numbering all teeth and detecting dental diseases, such as tooth caries, infections, impacted teeth, extracted teeth, and implants. The program for dental diseases correctly predicted 1,379 (true positive [TP]) out of 1,591 fillings and mismarked 397 healthy teeth (false positive [FP]). The AI detected fillings with a precision of 0.78, a recall of 0.85, and an F1 score of 0.82, with an average precision of 79.4%. The program correctly predicted 233 (TP) out of 245 implants and mismarked 11 healthy teeth (FP). The AI detected implants with a precision of 0.95, a recall of 0.95, and an F1 score of 0.95, with an average precision of 86.9%. The program for tooth enumeration correctly predicted 2,069 (TP) out of 2,241 teeth in Quadrant 1 and mismarked 277 teeth (FP). The AI detected teeth in Quadrant 1 with a precision of 0.92, a recall of 0.85, and an F1 score of 0.90, with an average precision of 82.1%. The tested and developed AI program can assist in evaluating dental diseases through two-dimensional panoramic radiographs; it can provide additional information to dentists to ensure accurate evaluation by jointly reporting tooth numbering and diagnosis. |

INTRODUCTION / INTRODUÇÃO

Accurate diagnosis is an important step for successful treatment in dentistry. Today, panoramic X-rays and clinical examinations are the most commonly used methods in dental diagnosis. Panoramic X-rays provide information on conditions such as dental anomalies, impacted teeth, chronic infections, and cysts that the dentist may not usually notice during oral examinations, as well as information on caries cavities, bone loss, and the quality of old dental treatments. To ensure correct diagnosis through X-rays, which is important to the patient, medical professionals must have many years of experience developing the necessary knowledge and skills. Artificial intelligence (AI) can interpret the obtained data and may provide results with similar accuracy to humans but in less time (1).

The AI concept (i.e., using machines to perform tasks traditionally achieved with human power/thought) first appeared in the 1950s (2). Machine learning (ML) is a subfield of AI that seeks to analyze patterns in data to advance decision-making and learning. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are a subfield of ML. They are one of the different types of artificial neural networks used for different applications and data types. A CNN is a type of network architecture for deep learning algorithms and is used explicitly for tasks that involve processing pixel data and image recognition (3). The CNN algorithm works by obtaining an image, assigning it some importance based on its different objects, and then distinguishing images from each other. A CNN needs much less pre-processing than other classification algorithms. Unlike conventional hand-engineered methods, a CNN can learn the characteristics and filters with sufficient training. The CNN’s design is analogous to the connectivity pattern of the human brain and its billions of neurons: A CNN comprises neurons arranged in a specific manner. Indeed, a CNN’s neurons are arranged in a way comparable to the brain’s frontal lobe, the area responsible for processing visual stimuli. Like neurons in the human brain, a CNN can learn and be diagnostic when provided with sufficient sample image data (4). The most commonly used deep learning architecture in dentistry is a CNN employing a convolutional process to learn from data (5).

CNNs have been used in dental diagnostics for automatically segmenting teeth (6,7) and for detecting caries (8,9), apical lesions (10), and periodontal bone loss (11). In modern dentistry, CNNs may contribute to correct and early diagnoses (10), such as detecting oral cancers and cysts at their initial stages, preventing damage to healthy tissues, and detecting caries and periodontal diseases, potentially resulting in less invasive dental procedures (12).

To our knowledge, no published studies have used a deep learning model to simultaneously diagnose dental diseases, identify old dental treatments, and number teeth. This study aimed to evaluate the efficiency of a CNN method to provide a broad spectrum for dental diagnosis.

METHODS

Imaging Data Selection

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Istanbul Medipol University (10840098-604.01.01-E53838). Overall, 5,126 digital panoramic radiographs of patients aged 13–65 years were selected from the Faculty of Dentistry’s archive at Istanbul Medipol University. Panoramic X-ray films were randomly selected and anonymized from the faculty hospital’s database without considering or using personal information such as name, sex, age, and address. All panoramic radiographs were obtained with a Planmeca Promax 2D Panoramic System (Planmeca, Helsinki, Finland) at 68 kVp, 14 mA, and 12 s.

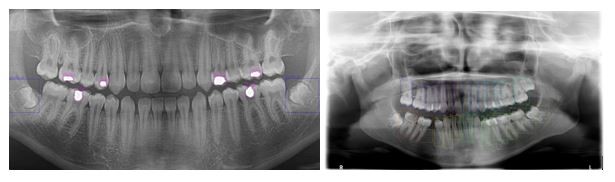

The issues described Section 1 are open problems, which were challenging to overcome. Studies have attempted to pinpoint tooth location and enumeration on panoramic X-ray images. However, identifying multiple concurrent treatments remains an unsolved task. Each treatment and enumeration in the maxillae and the mandible were manually annotated by labeling the bounding box in the LabelImg program (13). The locations of diagnosis and numbering were marked by drawing a bounding box, and all teeth were labeled in our study (Fig. 1). The 5,126 radiographs in the dataset contained 56,520 tooth treatments and 95,066 tooth numbers, which were used as the ground truth data for training and testing. The test data comprised 10% of the panoramic radiographs.

Figure 1. Detections from treatment (Blue labels Impacted Tooth and Purple labels Filling) and enumeration data set.

Artificial Intelligence Model Development

CNNs, one of the most popular architectures for deep learning, are commonly used for object recognition and detection (9). Object detection methods are classified as one- and two-stage detectors. CNNs are designed to cover the entire image with cells in the visual center (14). Subregions are divided into simple and complex cells. Simple cells are arranged according to the similar features of the edges, and complex cells are arranged according to the whole image with wide sensors (15).Mathematical convolution operations calculate the signals of neurons in the stimulation area. Like a standard multilayer neural network, a CNN comprises at least one convolutional layer, a nonlinear activation layer, a subsampling layer, and at least one fully connected layer. CNN models are applied in many areas, including audio and video processing (16,17). This study applied a CNN model, which is widely used in many biomedical fields. One of the most important reasons for using a CNN was to create a model with high generalization capability that could be applied to panoramic radiographs obtained with different systems.

The you only look once (YOLO) architecture, the most noticeable model of one-stage detectors, can detect and classify objects in a single image. YOLO is a real-time object detection model that detects multiple objects and draws bounding boxes around each object to indicate the detection area (18).YOLO version four (YOLOv4) was designed to detect objects in real time (19). It is recognized as a highly accurate model with an optimal trade-off between speed and object detection performance (20). The YOLOv4 model used in this study is a state-of-the-art model for object detection in images. It achieves very fast inferences in detecting treatment and tooth numbering in radiographs. CSPDarknet53 was used as the backbone network for YOLOv4.

The model was developed and trained using Python’s PyTorch deep learning framework (21). Radiology image datasets were randomly divided into training and test sets. Out of 5,126 panoramic images, 4,627 numbering and 4,626 treatment images were used for training, and the remaining 499 numbering and 500 treatment images were used for testing.

The images were resized to 608 × 608 pixels for model training, conducted on a server with an Nvidia RTX2080 Ti (11 GB of RAM; Nvidia Corp., Santa Clara, CA, USA) graphics card and 192 GB of RAM. The model was trained for 100 epochs. The Adam optimizer was used during training with a learning rate of 0.001. The batch size was set as 32, and the subdivision value was set as 4. Two separate YOLOv4 models were trained: one for tooth numbering and one for dental diagnosis.

The Set of Artificial-Intelligence Machine Learning Models

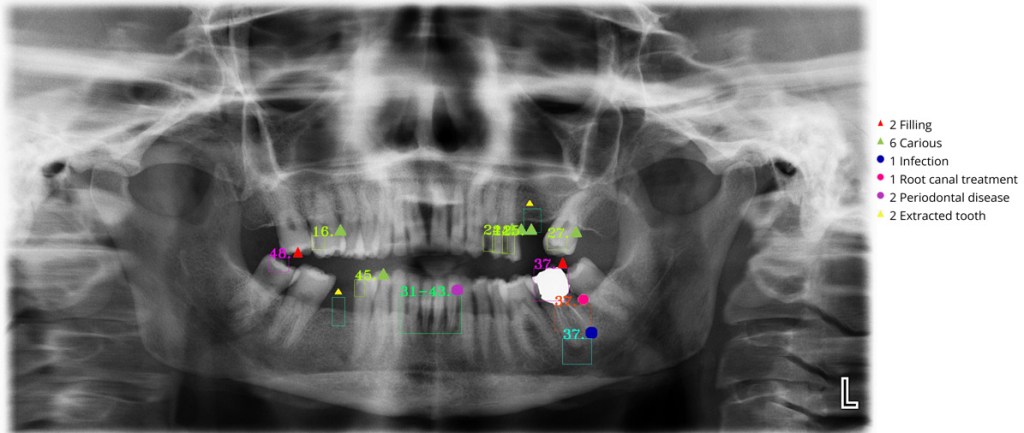

This study aimed to identify tooth numbering and dental treatments in X-ray images, such as implants, infections, caries, fillings, root canal treatments, extracted teeth, impacted teeth, bridges, and crowns (Fig. 2 and 3).

Figure 2. 2D images for tooth treatment.

In the enumeration model, treated as an object detection task, the individual tooth numbers are found and tagged according to the International Dental Federation notation. This notation includes 11, 12, 13, 14….44, 45, 46, 47, and 48 numbers for 32 total classes. In addition, this numbering represents four quadrants (Quadrant 1: 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18).

Like the enumeration model, the treatment detection model takes a full panoramic radiograph as input and attempts to identify the necessary diagnosis using object detection. It was also based on YOLOv4 architecture.

Figure 3. Dental AI application results.

Combining Both Models

The detection outputs of both treatment and enumeration models are combined to detect and visualize the problematic teeth. Therefore, the detected tooth numbers are matched with the detected dental treatments to determine which teeth have dental diagnoses. For this purpose, each treatment bounding box is intersected with the bounding boxes of the numbered teeth, and the intersection ratio is computed as

where and are the treatment and enumeration bounding boxes, respectively. The number of the tooth with the maximum intersection ratio is then determined. If this maximum intersection ratio is >25%, that treatment is associated with that tooth number. If the maximum ratio is <25%, the treatment is not matched to any tooth. For bridges and periodontal disease, as these issues are associated with more than one tooth, all intersecting teeth are determined. If the total intersection ratio is >25% and the teeth are consecutive in the mouth, the treatment is matched to all intersecting teeth.

Statistical Analysis

The YOLOv4 model’s detection accuracy was evaluated based on the true positive (TP), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN) rates. Correct treatment and enumeration detections were defined as TPs, incorrect detections as FPs, and missing detections as FNs. The indices used for object detection assessment included precision, recall, F1 score, and average precision (AP).

Precision was calculated as the ratio of TPs in the predicted samples to all positive results. Recall was calculated as the ratio of TPs to all results that should be positive. The F1 score was calculated as the harmonic mean of precision and recall. AP was calculated as the area under the precision–recall curve.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and Python 3 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) in Jupyter (NumFOCUS Foundation, Austin, TX, USA). When assessing permanent tooth germ detection in YOLOv4, confidence values were analyzed with true values coded as “1” and false values as “0.”

RESULTS

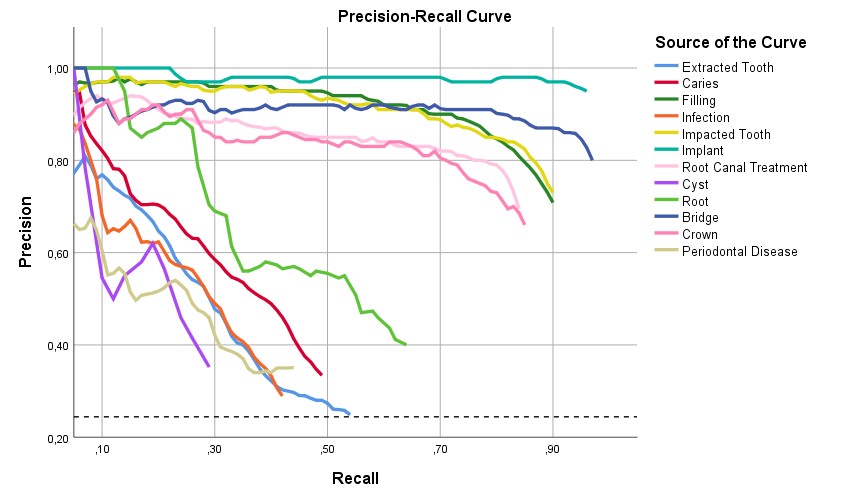

The ability to make correct diagnoses was tested on 5,652 samples from adult patients. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 26.0; IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). TP, FP, and FN detections were determined based on the program’s output, and receiver operating characteristic analysis was performed on the resulting dataset. We used the following metrics to evaluate our method’s performance: precision, recall (Figure 4), F1 score, and AP.

Figure 4. Precision-recall curve for tooth diseases.

Treatment Detection

The program correctly predicted 1,379 (TP) out of 1,591 fillings and mismarked 397 healthy teeth (FP). The AI detected fillings with a precision of 0.78, a recall of 0.85, and an F1 score of 0.82, with an AP of 79.4%. The program correctly predicted 269 out of 282 bridges and mismarked 51 healthy teeth. The AI detected bridges with a precision of 0.84, a recall of 0.95, and an F1 score of 0.89, with an AP of 80.5%. The program correctly predicted 233 out of 245 implants and mismarked 11 healthy teeth. The AI detected implants with a precision of 0.95, a recall of 0.95, and an F1 score of 0.95, with an AP of 86.9% (Table 1).

The program correctly predicted 102 out of 324 infections and mismarked 117 healthy teeth. The AI detected infections with a precision of 0.47, a recall of 0.31, and an F1 score of 0.37, with an AP of 41.2%. The program correctly predicted 51 out of 203 periodontal disease cases and mismarked 48 healthy teeth. The AI detected periodontal disease with a precision of 0.52, a recall of 0.25, and an F1 score of 0.34, with an AP of 42.6%. The program correctly predicted 12 out of 42 cyst cases and mismarked 16 healthy teeth. The AI detected cysts with a precision of 0.43, a recall of 0.29, and an F1 score of 0.34, with an AP of 39.7% (Table 1).

Table 1. Performance of the AI for the detection of diagnosis on adult patients.

| Diagnosis Sample | TP | FP | FN | Precision | Recall | F1 | AP | p | |

| Filling | 1591 | 1379 | 397 | 212 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.794 | 0.001 |

| Bridge | 282 | 269 | 51 | 13 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.805 | 0.001 |

| Implant | 245 | 233 | 11 | 12 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.869 | 0.001 |

| Bracket | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| Root Canal Treatment | 714 | 590 | 199 | 124 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.764 | 0.001 |

| Carious | 973 | 359 | 339 | 614 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.556 | 0.01 |

| Impacted Tooth | 345 | 304 | 89 | 41 | 0.77 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.808 | 0.001 |

| Infection | 326 | 102 | 117 | 224 | 0.47 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.412 | 0.33 |

| Cyst | 42 | 12 | 16 | 30 | 0.43 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.397 | 0.486 |

| Periodontal Disease | 203 | 51 | 48 | 152 | 0.52 | 0.25 | 0.34 | 0.426 | 0.311 |

| Crown | 116 | 92 | 33 | 24 | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.764 | 0.001 |

| Root | 66 | 36 | 29 | 30 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.568 | 0.001 |

| Extracted Tooth | 749 | 253 | 376 | 496 | 0.4 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.453 | 0.014 |

AI: Artificial intelligence, TP: True positive, FP: False positive, FN: False negative, AP: Average precision.

Based on these results, the most successful AI diagnoses were fillings, bridges, implants, and impacted teeth, whereas the most unsuccessful diagnoses were infections, periodontal disease, and cysts. Although there were no bracket diagnoses among the assessed samples, it was determined that the program mismarked this diagnosis on four teeth.

It has been shown that AI tends to provide accurate results, especially for filling, bridge, implant, and impacted tooth detection. However, the program tends to misdiagnose healthy teeth with infections, periodontal disease, and cysts.

Tooth Enumeration

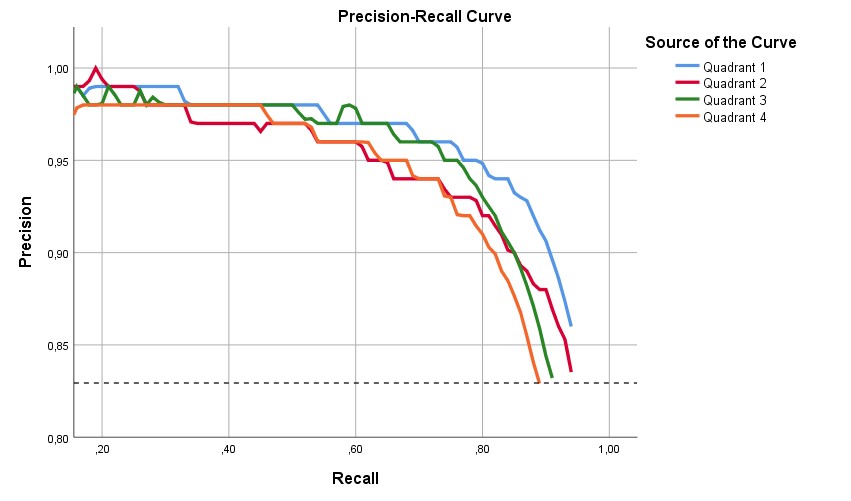

The program correctly predicted 2,069 (TP) out of 2,241 teeth in Quadrant 1 and mismarked 277 (FP). The AI detected teeth in Quadrant 1 with a precision of 0.92, a recall of 0.85, and an F1 score of 0.90, with an AP of 82.1%. The program correctly predicted 2,033 (TP) out of 2,191 teeth in Quadrant 2 and mismarked 335 (FP). The AI detected teeth in Quadrant 2 with a precision of 0.91, a recall of 0.83, and an F1 score of 0.87, with an AP of 80.4%. The program correctly predicted 2,302 (TP) out of 2,574 teeth in Quadrant 3 and mismarked 408 (FP). The AI detected teeth in Quadrant 3 with a precision of 0.91, a recall of 0.84, and an F1 score of 0.87, with an AP of 77.3%. The program correctly predicted 2,168 (TP) out of 2,494 teeth in Quadrant 4 and mismarked 366 (FP). The AI detected teeth in Quadrant 4 with a precision of 0.91, a recall of 0.81, and an F1 score of 0.86, with an AP of 75.8% (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Quadrant of Jaw’s precision-recall curve.

It has been shown that, though AI-based tooth numbering was generally accurate in all quadrants, it was the most accurate in Quadrant 1 (Table 2).

Table 2. Performance of the AI for the detection of tooth number on adult patients.

| Sample | TP | FP | FN | Precision | Recall | F1 | AP | p | |||

| Quadrant 1 | 2241 | 2069 | 277 | 172 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.821 | 0.001 | ||

| Quadrant 2 | 2191 | 2033 | 335 | 158 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.804 | 0.001 | ||

| Quadrant 3 | 2574 | 2305 | 408 | 269 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.773 | 0.001 | ||

| Quadrant 4 | 2494 | 2168 | 366 | 326 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.849 | 0.001 |

AI: Artificial intelligence, TP: True positive, FP: False positive, FN: False negative, AP: Average precision.

DISCUSSION

Improvements in deep learning and neural methods have increased the use of AI in the medical field. In particular, in the field of dentistry, AI is being increasingly used on a daily basis due to its ability to solve clinical problems. Most previous studies aimed to use AI in dentistry to diagnose caries, periodontal diseases, and periapical lesions as well as to number teeth (6-11).

Early and accurate diagnosis of dental diseases is important for preventing diseases and increasing treatment success. The greatest importance of early and accurate diagnosis is catching the diseases at their initial stage, thereby preventing a process that may lead to tooth loss from the onset. For example, if enamel caries are not detected early, they can progress and damage the dentin pulp and even periodontal tissues. Moreover, a periodontal disease that progresses unnoticed can cause advanced bone loss and even tooth loss. A deep CNN-based algorithm may provide significant success and effectiveness in detecting such dental problems.

The YOLO architecture is based on a single CNN. The CNN first segments an image into regions and then individually estimates boundary boxes and probabilities for all regions. It simultaneously estimates multiple bounding boxes and the probabilities for those classes. The YOLO model can observe the whole image during the test and training periods so it can indirectly encode the contextual information about the classes along with them.

This study explored the benefits and limitations of the YOLOv4 CNN algorithm in detecting dental diseases (caries, periapical infections, cysts, periodontal diseases, and residual root fragments), previous treatments (fillings, bridges, crowns, root canal treatments, implants, and previously extracted teeth), and tooth numbers in panoramic images. YOLOv4 is a successful real-time detection system that can classify targeted objects in a single forward pass (22). Moreover, YOLOv4 treats detection as a regression problem that does not need a complicated pipeline or semantic segmentation. YOLOv4 can also jointly learn test regions and their background and make inferences for other images to predict detections during testing (23). YOLO was selected over other CNN models due to its speed and real-time ability in detecting objects.

Indeed, YOLO’s best differentiating feature is that it can accurately perform real-time object detection with an overall high mean AP (22).

We could not find a published study covering different dental diseases, previous treatments, and tooth numbering as comprehensively as ours. These different areas provided us with a number of interesting findings. AI did not provide as accurate results as we would like in diagnosing dental diseases. The AP was 55.6% for caries, 41.2% for periapical infections, 39.7% for cysts, and 42.6% for periodontal disease. However, the success rates in diagnosing old treatments and numbering teeth were approximately two times better compared with diagnosing diseases. The AP was 79.4% for fillings, 80.5% for bridges, 86.9% for implants, and 76.4% for root canal treatments and crowns. In addition, success rates in tooth numbering varied between 77.3% and 84.9%, depending on the quadrant.

In our study, three different specialist dentists contributed to labeling dental diseases and other data for the program. Diseases (periodontal disease, caries, and periapical lesions) are labeled in radiographs according to relatively subjective criteria. Different dentists may have different opinions when diagnosing disease in X-rays. The AI’s ability to detect diseases in X-rays highly depends on the examiner’s experience and attention, which are highly subjective. However, in our study, AI provided satisfactory results in diagnosing previous treatments. We believe this is because the labeling of previously performed treatments is based on more objective data compared with new diseases. It should be noted that diagnosing new diseases via radiography may vary according to dentists’ experience.

The importance of radiography in diagnosing root and interproximal caries alongside intraoral examination is a well-known issue (24). In studies conducted with different methodologies on this subject, the success rates of clinicians in detecting caries were 38%–94% for proximal caries and 19%–92% for occlusal caries (25). Another study reported that approximately 20% of images were misdiagnosed as dental caries. It is challenging to objectively diagnose caries based only on radiography because of variable parameters such as contrast, shadow, and brightness (26,27). For example, >50% of the tissue must be affected to diagnose enamel caries. In addition, the incidence and prevalence of dental caries may be inconsistent due to differing caries diagnosis and identification criteria between studies (28).

In our study, the AI detected periapical infections with an AP of 41.2% and cysts with an AP of 39.7%. At first glance, this may suggest that AI is insufficient for detecting pathologies in the periapical region of the teeth. To ensure precise diagnosis, in addition to X-rays, clinical symptoms are considered, such as swelling or sinus tract, when assigning the periapical lesion in the tooth.

Moidu et al. (29) used AI to categorize endodontic lesions based on a radiographic periapical index (PAI) scoring system. Their TP rate for periapical status was about 92% when PAI scores of 3–5 were specified as periapical lesions. The radiography method was the main reason for differences in prediction success between studies. Moidu et al. (29) used an intraoral periapical radiograph to detect periapical lesions. However, our study used extraoral panoramic radiographs, which are less detailed than intraoral periapical radiographs, because we aimed to detect multiple dental diseases in the patients.

Krois et al. (11) used deep CNNs to detect periodontal bone loss in panoramic dental radiographs. According to their findings, the CNN’s mean accuracy for detecting periodontal bone loss was 81%, and the mean accuracy for dentists was 76%. Notably, they stated that the six examiners agreed on periodontal bone-loss status only for 50.3% of images. Our study’s criterion for periodontal disease was apparent bone loss in panoramic X-rays. Dentists can make different decisions when diagnosing diseases in X-rays, as in Krois et al (11). We believe this is the main reason for our study’s relatively low diagnostic success for periodontal diseases.

Tuzoff et al. (30) used CNN-based models to analyze panoramic radiographs. They attempted to describe the maxillar and mandibular jaws within a single image using a CNN-based deep learning model trained to detect and number teeth during automated dental charting. Their result for tooth numbering was 98.93%. They claimed that AI deep learning algorithms have potential practical applications in clinical settings. Our success rates for numbering varied between 77.3% and 84.9%. The differing success rates between their study and ours likely reflect differences in modeling and CNN architectures. Their algorithm clipped the panoramic X-rays due to the defined bounding boxes. The system outputs the bounding box coordinates and corresponding teeth numbers for all detected teeth in the image. In contrast, our CNN model took the full panoramic radiograph as input and tried to identify the necessary diagnosis using object detection.

Like all standard radiographs, panoramic X-rays show a three-dimensional structure in two dimensions. In this case, some anatomical structures may superimpose and cause problems in image interpretation (31). This factor was one of the most challenging issues for dentists contributing to labeling in our study.

In this study, a CNN model was trained and used to number teeth and detect dental diseases such as tooth caries, infections, impacted teeth, extracted teeth, and implants. The CNN algorithms could be used in diagnostic tasks involving panoramic radiographs, specifically for dental diseases and tooth numbering. The system achieved an average performance for dental diseases and satisfying results for tooth numbering. The detailed error analysis showed that experts made errors due to similar problems in the images, especially when the image quality was relatively poor. Based on our results, our CNN could be used for tooth numbering. However, its use in diagnosing dental diseases needs further development. Integrating the patient’s history, symptoms, and clinical complaints in the deep learning system may improve decision-making and diagnostics with extraoral radiographs.

We believe such studies need more examples to train their systems to obtain better results. Although our model did not provide satisfactory results for disease identification, it was relatively efficient in tooth numbering. A limitation of this study is that three different dentists made the disease decisions. As differences between findings are sometimes due to nuances, the difficulties experienced by three different researchers while making decisions may be one main reason for these rates.

Based on our study’s findings, CNNs show potential for tooth enumeration and old treatment detection in clinical decision-making. Their use would be beneficial for large-scale retrospective or epidemiological radiological studies, where the volume of data could be tiring and distracting for human observers. However, more detailed radiographic images (e.g., cone-beam computed tomography) should be used to enable more objective and successful disease diagnoses. Moreover, labeling standards should be set among dentists to improve disease diagnosis.

Conflict of Interest Declaration

No conflict of interest was declared by the authors in this study.

Declaration of Institutional and Financial Support

This study received no financial support.

Author Contributions

Sıtkı Selçuk Gökyay: Project administration, Writing- Critical review and editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation. Hüseyin Gürkan Güneç: Writing- original draft, Data curation, Visualization, Resources, Formal analysis. Investigation. Hasan Fehmi Ateş: Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Supervision.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval of the study was received.

CC BY Licence

This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

REFERENCES

- Murphy M, Killen C, Burnham R, Sarvari F, Wu K, Brown N. Artificial intelligence accurately identifies total hip arthroplasty implants: a tool for revision surgery. Hip Int. 2022;32(6):766-770. doi:10.1177/1120700020987526

- Amisha, Malik P, Pathania M, Rathaur VK. Overview of artificial intelligence in medicine. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(7):2328-2331. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_440_19

- Schwendicke F, Samek W, Krois J. Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry: Chances and Challenges. J Dent Res. 2020;99(7):769-774. doi:10.1177/0022034520915714

- Schwendicke F, Golla T, Dreher M, Krois J. Convolutional neural networks for dental image diagnostics: A scoping review. J Dent. 2019;91:103226. doi:10.1016/j.jdent.2019.103226

- Hiraiwa T, Ariji Y, Fukuda M, et al. A deep-learning artificial intelligence system for assessment of root morphology of the mandibular first molar on panoramic radiography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2019;48(3):20180218. doi:10.1259/dmfr.20180218

- Lee JH, Han SS, Kim YH, Lee C, Kim I. Application of a fully deep convolutional neural network to the automation of tooth segmentation on panoramic radiographs. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2020;129(6):635-642. doi:10.1016/j.oooo.2019.11.007

- Mahdi FP, Motoki K, Kobashi S. Optimization technique combined with deep learning method for teeth recognition in dental panoramic radiographs. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):19261. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-75887-9

- Devito KL, de Souza Barbosa F, Felippe Filho WN. An artificial multilayer perceptron neural network for diagnosis of proximal dental caries. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106(6):879-884. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.03.002

- Lee JH, Kim DH, Jeong SN, Choi SH. Detection and diagnosis of dental caries using a deep learning-based convolutional neural network algorithm. J Dent. 2018;77:106-111. doi:10.1016/j.jdent.2018.07.015

- Ekert T, Krois J, Meinhold L, et al. Deep Learning for the Radiographic Detection of Apical Lesions. J Endod. 2019;45(7):917-922.e5. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2019.03.016

- Krois J, Ekert T, Meinhold L, et al. Deep Learning for the Radiographic Detection of Periodontal Bone Loss. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):8495. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44839-3

- Rallan M, Rallan NS, Goswami M, Rawat K. Surgical management of multiple supernumerary teeth and an impacted maxillary permanent central incisor. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009995. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-009995

- Tzutalin D. LabelImg. https://github.com/tzutalin/labelImg, accessed: 13.04.2022.

- Moutselos K, Berdouses E, Oulis C, Maglogiannis I. Recognizing Occlusal Caries in Dental Intraoral Images Using Deep Learning. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2019;2019:1617-1620. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2019.8856553.

- Nielsen KB, Lautrup ML, Andersen JK, Savarimuthu TR, Grauslund J. Deep learning-based algorithms in screening of diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review of diagnostic performance. Ophthalmol Retina. 2019;3:294-304.

- Chartrand G, Cheng PM, Vorontsov E, et al. Deep learning: a primer for radiologists. Radiographics. 2017;37:2113-2131.

- Shakya KS, Laddi A, Jaiswal M. Automated methods for sella turcica segmentation on cephalometric radiographic data using deep learning (CNN) techniques. Oral Radiol. 2023;39(2):248-265. doi:10.1007/s11282-022-00629-8

- Almalki YE, Din AI, Ramzan M, et al. Deep Learning Models for Classification of Dental Diseases Using Orthopantomography X-ray OPG Images. Sensors (Basel). 2022;22(19):7370. doi:10.3390/s22197370

- Wang R, Wang Z, Xu Z, et al. A Real-Time Object Detector for Autonomous Vehicles Based on YOLOv4. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2021;2021:9218137. doi:10.1155/2021/9218137

- Parico AIB, Ahamed T. Real Time Pear Fruit Detection and Counting Using YOLOv4 Models and Deep SORT. Sensors (Basel). 2021;21(14):4803. doi: 10.3390/s21144803.

- Ziller A, Usynin D, Braren R, Makowski M, Rueckert D, Kaissis G. Medical imaging deep learning with differential privacy. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13524. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93030-0.

- Redmon JDS, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. arXiv [Internet]: 2015 Jun [cited 2022 Apr 13]. Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/1506.02640.

- Yang H, Jo E, Kim HJ, et al. Deep learning for automated detection of cyst and tumors of the jaw in panoramic radiographs. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1839.

- Abesi F, Mirshekar A, Moudi E, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of digital and conventional radiography in the detection of non-cavitated approximal dental caries. Iran J Radiol. 2012;9(1):17-21. doi:10.5812/iranjradiol.6747

- Bader JD, Shugars DA, Bonito AJ. Systematic reviews of selected dental caries diagnostic and management methods. J Dent Educ. 2001;65(10):960-968.

- Costa AM, Bezzerra AC, Fuks AB. Assessment of the accuracy of visual examination, bite-wing radiographs and DIAGNOdent on the diagnosis of occlusal caries. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2007;8(2):118-122. doi:10.1007/BF03262580

- Costa AM, Paula LM, Bezerra AC. Use of Diagnodent for diagnosis of non-cavitated occlusal dentin caries. J Appl Oral Sci. 2008;16(1):18-23. doi:10.1590/s1678-77572008000100005

- Selwitz RH, Ismail AI, Pitts NB. Dental caries. Lancet. 2007;369(9555):51-59. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60031-2

- Navas P Moidu, Sidhartha Sharma, Amrita Chawla, Vijay Kumar, Ajay Logani. Deep learning for categorization of endodontic lesion based on radiographic periapical index scoring system. Clin Oral Investig 2022;26(1):651-658. doi: 10.1007/s00784-021-04043-y..

- Tuzoff DV, Tuzova LN, Bornstein MM, et al. Tooth detection and numbering in panoramic radiographs using convolutional neural networks. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2019;48(4):20180051. doi:10.1259/dmfr.20180051

- Oz U, Orhan K, Abe N. Comparison of linear and angular measurements using two-dimensional conventional methods and three-dimensional cone beam CT images reconstructed from a volumetric rendering program in vivo. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2011;40(8):492-500. doi:10.1259/dmfr/15644321